Consider: Claiming My Own Hand

Respecting the Only Line That's Mine

I feel more confident as an illustrator than I ever have. And, I love to draw.

But while I’ve wanted to be an illustrator since I was a little kid, I have not always loved to draw. I have not always been proud of my work. I have not always believed that it was something I could seriously pursue. I have not always felt talented or creative enough.

Getting to this current point in my practice has been an uphill walk for years and years. And, while I feel good now, I know I’m nowhere near the top of the art-making mountain (or, also, there is no top of the mountain).

But, I can identify some foundational realizations that helped me gain confidence in my work and faith in my own unique way of making art. And I think that’s worth sharing.

When I first began getting serious about illustration sometime in college, it was already a very popular medium on social media. This online ubiquity was both good and bad—for one, I had a lot of inspiration, working models of successful illustrators, and sometimes validation from an audience.

But, it also muffled my own voice for a long time. I saw so much work that I loved, and so I wanted to make work that I loved in the same way. I limited myself to the scope of what I was seeing—in short, if I liked this work other people were making and they found success with it, shouldn’t I make work like that too?

Of course, there are lots of flaws with this approach. For one, I can’t make work that is both my own and someone else’s. When I drew the subjects I saw other people drawing or used the tools everyone was using, my work felt shallow. It didn’t have heart or narrative behind it. It felt like a weak imitation, and of course, I was trying to imitate what was popular.

That being said, at least I was drawing. It got me to regularly work in my sketchbook and try things out. At that time, my technical skills were far from sufficient. So no matter the work I was intending to make, the results were falling short.

But, there were rare moments when I drew something I was proud of, that fit the “ideal” that I’d been aspiring toward or rose above my technical limitations—and still, something was missing. It was hollow. It was directionless.

And that led to my first important realization: Even though I like the work of X, Y, or Z, it is not the way I want my work to look.

This sounds simple, but it felt revolutionary. Work that was fulfilling and successful for me was not going to look like other work I admired. What would it look like? I had no idea. But at least I had started down my own path.

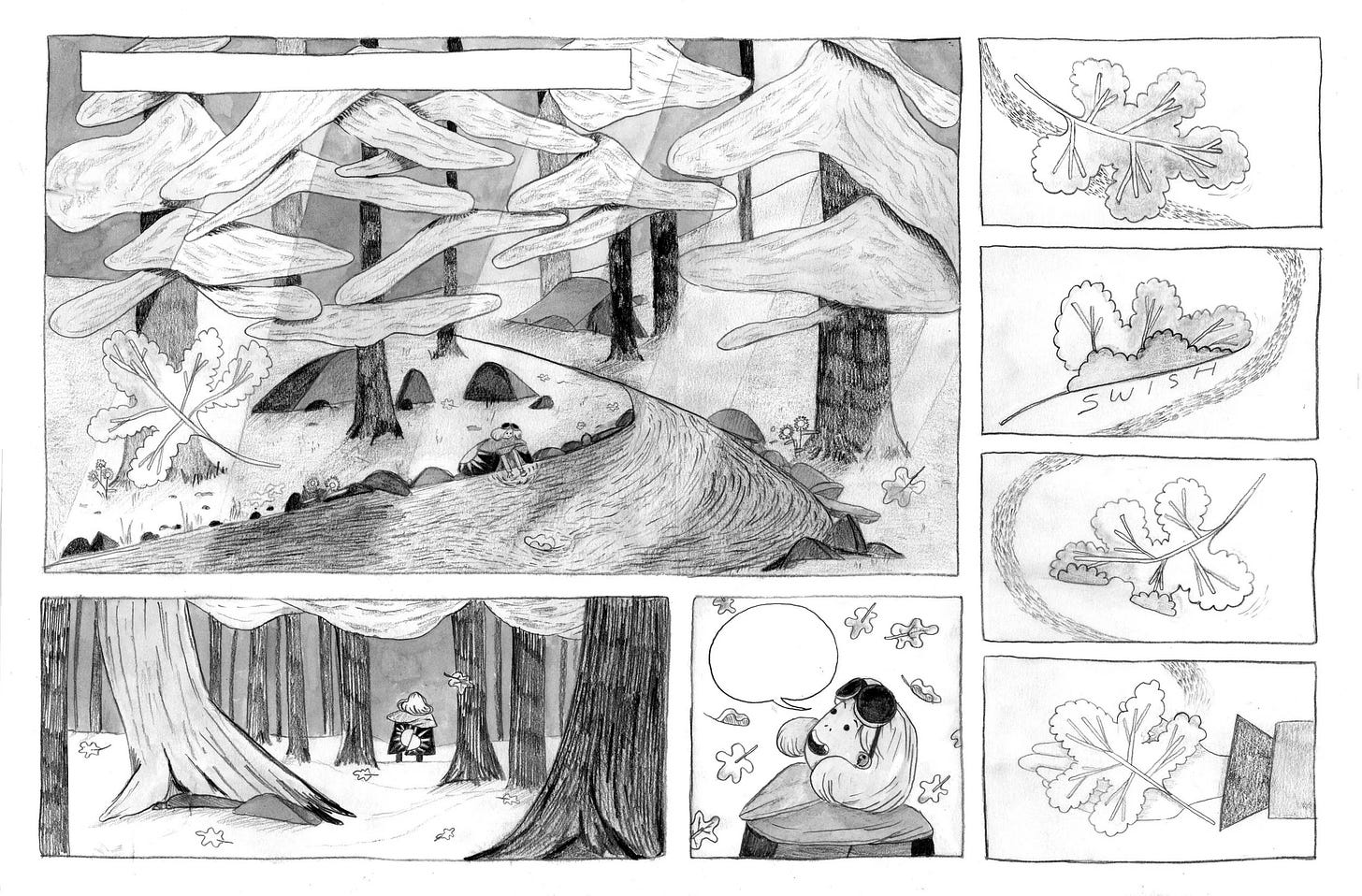

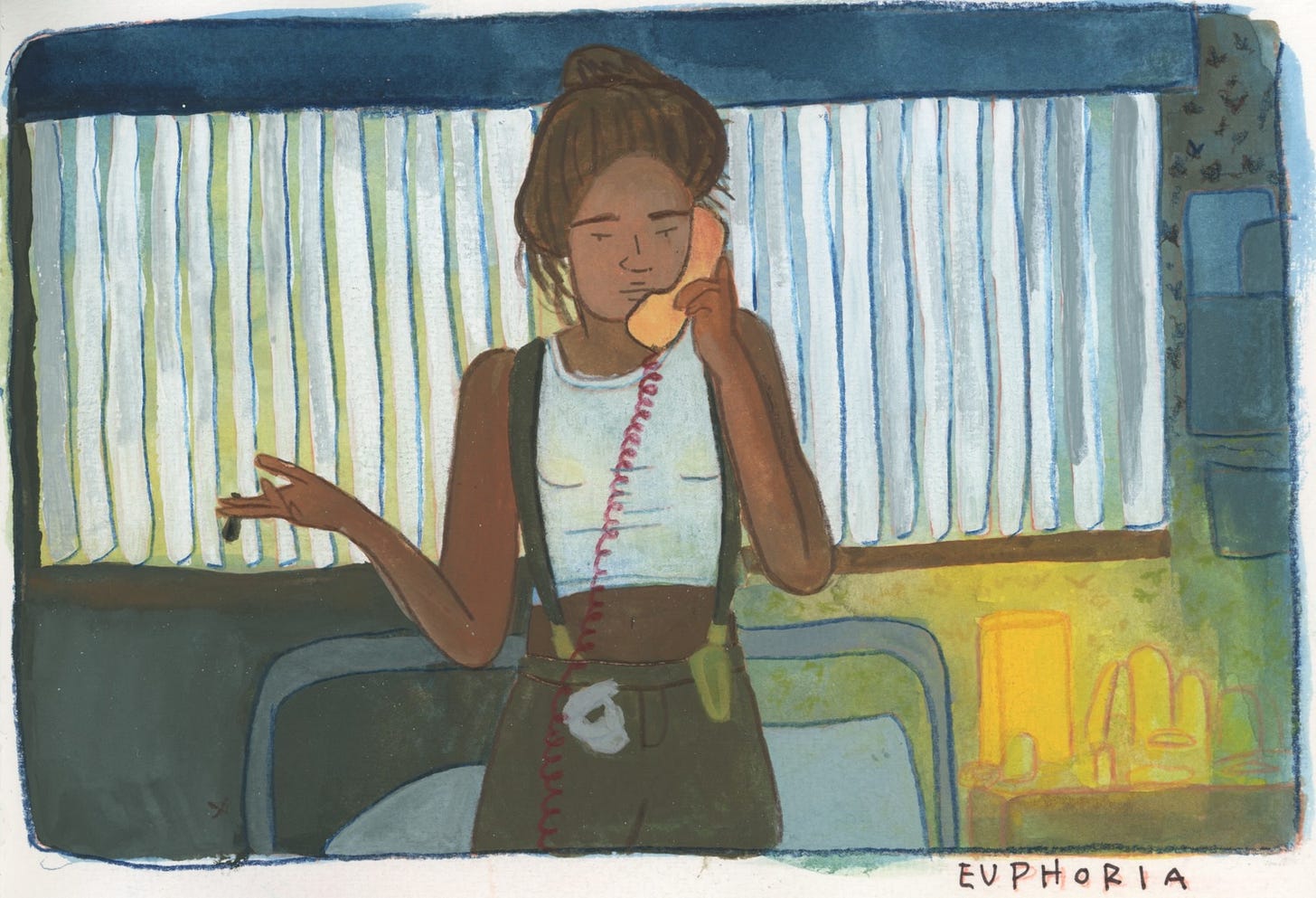

That path involved a lot of drawing. This is the only way to figure out what I care about as an illustrator. Not thinking about it or looking at other art—making art. This is the beginning of what I today call my illustration practice. For a while, I worked on this weekly series of movie and TV screencap paintings.

I really enjoyed them, and lots of scenes with backgrounds and characters and varied lighting did wonders for improving my technical skills. At the same time, I was drawing in my sketchbook most days and working toward more complete and detailed pieces month-by-month for a couple of years. It was the first time I was regularly working.

In some ways, you could say that this essay is about the idea of style. But it’s very much not about style in the way that I thought of it in that time (when it was also all over the place—there was so much content to “help you find your style.”).

It was pitched as a requirement—the idea that you must develop a single “look” for your art that informs the way you illustrate anything and everything, creating a cohesive portfolio that people can know you by.

I was distraught that I didn’t seem to have my own style in those years. Though I understand the appeal, I think it’s a very flawed way to think of your own development. A single visual language that you can apply to anything and get back beautiful results is magical; but the idea that style comes first, that you must develop your “look” before you can make real work is (in my experience) totally wrong.

It makes so much more sense (and is much less stressful) to just start developing work piece-by-piece instead of worrying about your look as a whole. I think the concept of style is a result of the idea that everything we do should be part of our brand or niche, which I find totally antithetical to being an artist and maker.

So, thinking about style in those terms fell away, and my work began to improve, things were coming together in 2023. I began to love drawing instead of fearing it. I found subjects that I cared about, so my work had heart behind it. I was working on picture book illustration for my own stories, which felt like my calling. During this time, I also did the Artist’s Way for the first time, which helped in developing healthy habits for my practice and mindset. Things were going well.

But still, often, it felt like there was something missing. I felt dissatisfaction with my work. I didn’t address it for a long time because I wasn’t sure where it came from, and I had improved so much compared to my early work, that it didn’t feel fair to keep doubting myself. But what was it? Was my work actually bad? Was I still not good enough to be doing this? Why hadn’t all this growth come with any confidence?

And then the beginning of the second realization hit me: I had not learned to accept the originality, the uniqueness, the inherent me that appears in my own work.

No matter what I draw, how I draw it, when, where, why—no matter what—everything I draw will always have my hand in it. My lines will always and only be my lines. I can, of course, get better, draw new things, use different mediums, improve technically, grow, change, make things I could never have made before—and still, everything I make will be indelibly tinged with the look of something only I can make.

This sounds like a beautiful, worthy thing. It’s what makes art special, certainly. But to a developing artist who has spent years knowing that the work isn’t there yet or comparing to other work, the idea that you won’t ever be able to make something that doesn’t read as “made by me” doesn’t always feel like a positive.

And so, then, when finally, years later, the work begins to be something worth writing home about, it’s not necessarily an easy switch to flip. To go from, Hey, my wobbly lines, skewed perspective, and totally singular art still needs a lot of work to Hey, I am grateful for my lines, my special visual voice, and my art that doesn’t look like anyone else’s is not an automatic transition.

When you are looking at work that is really and truly a result of your own, individual, particular practice, you will be asking yourself to evaluate something that is unlike anything you’ve exactly seen before. Unfortunately, our instinct as adult artists is not to meet newness and weirdness and rarity with acceptance, but instead to criticize it. Style is not something you invent, but something you bring out of yourself: slowly, through hard work, without artifice or construction.

Finding your way into accepting the singularity of your work, the precious, one-of-a-kind nature of your hand, is a really, really big deal!

There is an element to being an artist that is out of our control:

“The writer can choose what he writes about, but he cannot choose what he is able to make live.” - Flannery O’Connor

George Saunders touches on this subject really, really powerfully in A Swim In a Pond in the Rain (a real 5-star book!) in the context of being a writer. The following block quotes are all from that book.

When we find ourselves staring in the mirror at the artist we are—maybe the artist we are really seeing for the first time:

“This writer may bear little resemblance to the writer we dreamed of being. She is born, for better or worse, out of that which we really are: the tendencies we’ve been trying, all these years, in our writing and maybe even in our lives, to suppress or deny or correct, the parts of ourselves of which we might even feel a little ashamed.”

Whatever we are seeing now is almost certainly not what we imagined for ourselves. Before this moment, before this noticing of ourselves, this version of an artist has never existed.

“This is a big moment for any artist (this moment of combined triumph and disappointment), when we have to decide whether to accept a work of art that we have to admit we weren’t in control of as we made it and of which we’re not entirely sure we approve. It is less than we wanted it to be, and yet it is more, too.”

Which, I think, brings me to the third realization: Accepting, celebrating, and refining—claiming—my own hand is an essential step in my practice, my success, and my confidence.

When I began to respect my own special way of doing things, so much clicked into place. I don’t have to make art like anyone else. I don’t have to measure my success by anyone else’s standards. I am not scared to make “ugly” work; I’m much braver when I sit down at my desk, less judgmental about what shows up on the page. It is a powerful, important thing to make my art.

“I like what I like, and you like what you like, and art is the place where liking what we like, over and over, is not only allowed, but is the essential skill. How emphatically can you like what you like? How long are you willing to work on something to ensure that every bit of it gets infused with some trace of your radical preference? The choosing, the choosing, that’s all we’ve got.”

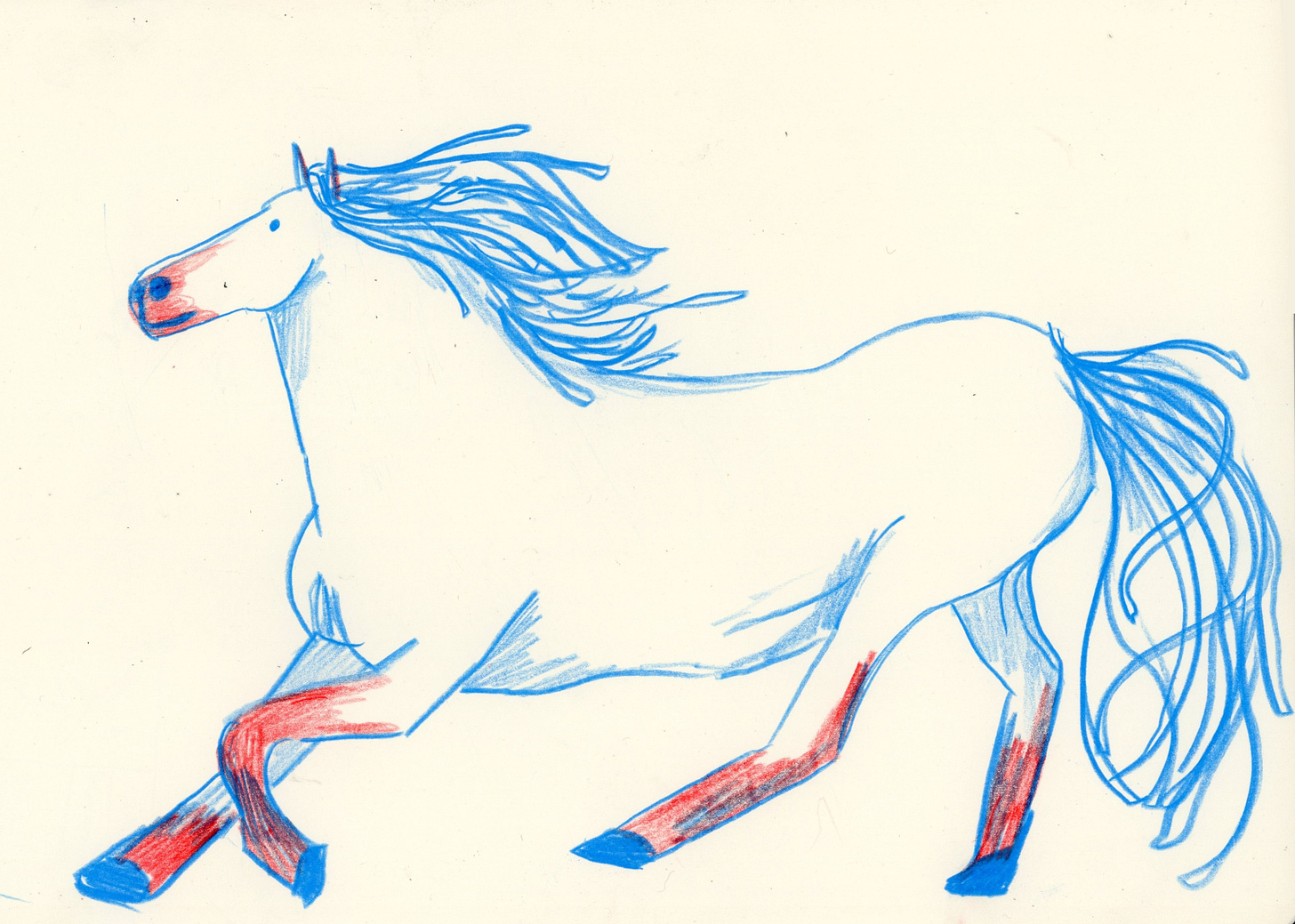

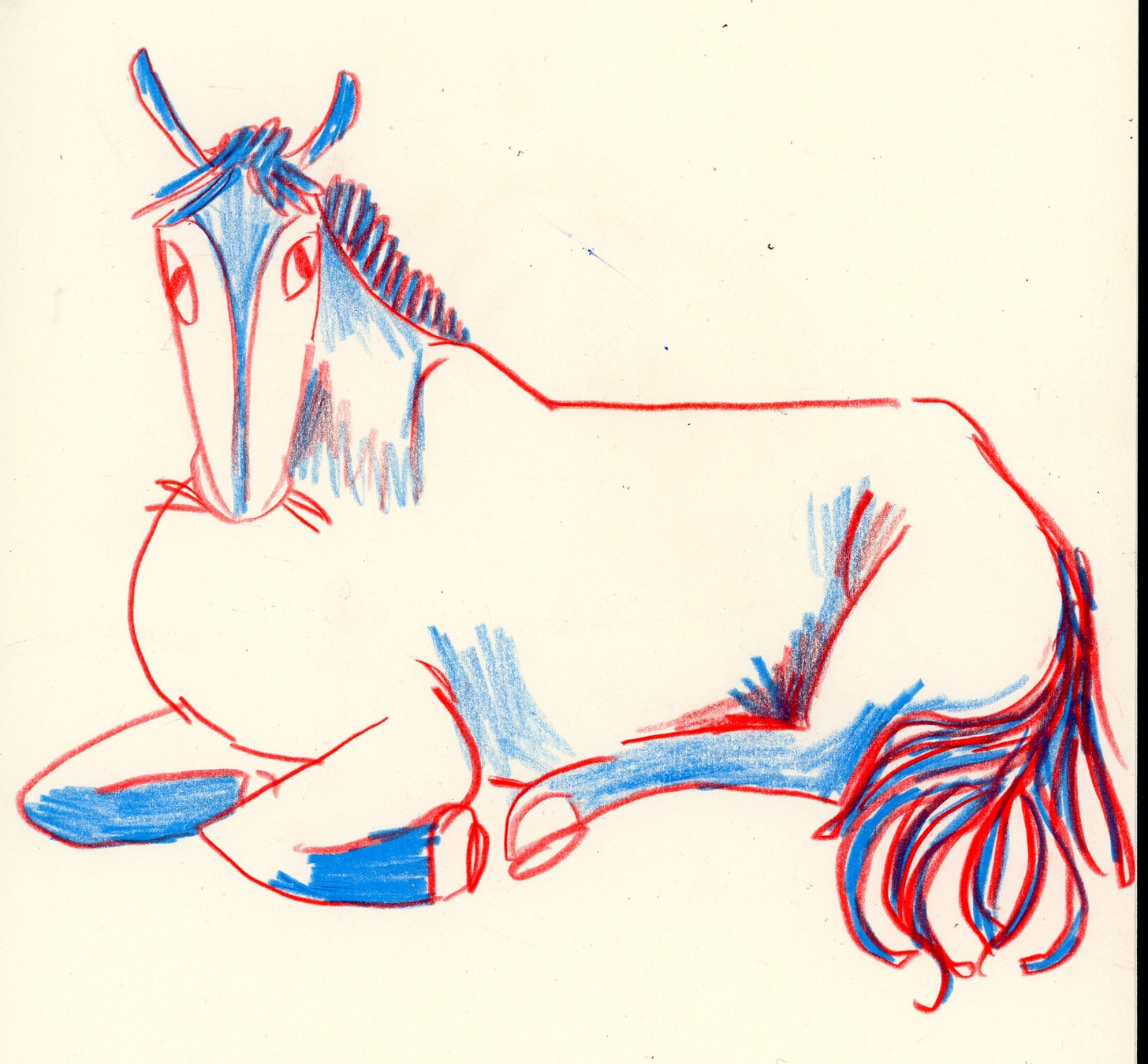

I guess what I’m saying is, give yourself a chance. Over and over, remind yourself that it’s worth giving your voice the ability to be heard. Take this horse, for example:

I wrote about this briefly in my Milkwood Part 1 post. During the residency, each artist was asked to draw a horse in a big tome of a sketchbook that sits in the barn’s main room. There are a dozen of these sketchbooks, each graced with pages and pages of original art from the incredible artists who have stayed at Milkwood.

It’s sort of a running joke in the illustration world that horses are difficult to draw. So when I saw this prompt, and then I spent time admiring the gorgeous (and I mean stunning) horses that were already in the book, I felt quite intimidated.

When I finally did sit down to practice for my horse, I drew the two you see here in my personal sketchbook. They were fast colored pencil drawings, meant to help me untangle the complicated anatomy of these unusual creatures so that I could contribute something, anything to the books of beauty up in the loft.

And, a half hour later, looking at these horses staring back up at me, I wanted to cry. Are these horses anatomically perfect, exactly as I would have imagined them, or anything like the other horses I saw in those books? No (see: tiny head, red and blue, lack of polish). And yet, I find them so beautiful. Only I could have drawn them. Only my hand—honed through hundreds of hours of work and earnestly ready to try—could have conjured them on the blank page. (P.S. You can see the finished painting I added to the Milkwood book in the post linked above).

When I sat down to draw them, I wasn’t feeling confident in my own hand. But these drawings quickly reminded me that even when a hundred other beautiful horses have come galloping along before mine, I have something to offer, something to celebrate, something that’s me.

Read more about me, my work, and my book journey at my website: madison-makes.com

I love this idea because I have learned it the hard way. Think of style as the voice you were given. If it is deep, learn to love the tarry dark tambre of it; if it is squeaky, think about how beloved Lamb Chop was. George Saunders is so right as is Madison Moore. Pretty good company, I think :-)

What a lovely ode to self love as an artist. I would have loved to read something like this years ago, when I was fresh out of college and despairing about my style, etc when I could have been fully present in the journey 🧡